On May 14, 2015, Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society hosted a live and public Google Hangout with its 2015 Young Investigator Award Winner, Dr. Melissa A. Kenny. A recording of the Google Hangout and a transcript are available on the bottom of this page.

Dr. Melissa A. Kenney is a research assistant professor in environmental decision analysis at the University of Maryland, Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center. Her research in environmental decision analysis broadly addresses how to integrate both scientific knowledge and societal values into policy decision-making under uncertainty.

Dr. Melissa A. Kenney is a research assistant professor in environmental decision analysis at the University of Maryland, Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center. Her research in environmental decision analysis broadly addresses how to integrate both scientific knowledge and societal values into policy decision-making under uncertainty.

This research is inherently multidisciplinary, drawing on the fields of decision theory, environmental sciences, and public policy. This research addresses a range of topics including global change indicators, nutrient criteria setting, non-market benefits of nutrient reductions, cost-benefit analysis of urban stream restoration, scale of economies and diseconomies in coastal restoration, adaptive environmental decision making for complex systems, model-based bias correction factors for expert elicitation surveys, and value of information of indicators.

These projects were published in a range of referred journals and reports, resulted in >$4.5M in grants funding, and has received numerous awards. From 2010-2012, Dr. Kenney was a research assistant scientist at The Johns Hopkins University and an American Association for the Advancement of Sciences (AAAS) Science and Technology Policy Fellow.

Recently and most notably, she has been the lead scientist on a team that worked toward developing recommendations and a prototype set of indicators to empower decision makers with the scientific information to understand and respond to climate changes and impacts.

The results of her team’s efforts were announced in May, 2015, as the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP) unveiled a set of pilot indicators that will serve as a proof-of-concept for its climate indicators. Kenney’s team provided input into the indicators that were ultimately adopted by USGCRP.

She received a B.A. with distinction in environmental sciences at the University of Virginia, a Ph.D. in water quality modeling and decision analysis from the Nicholas School of the Environment and Earth Sciences at Duke University, and was a postdoctoral scholar with the National Center for Earth-surface Dynamics.

Kenney joined Sigma Xi in 2005 and is a member of the University of Maryland Chapter. She helped to reactivate the Duke University Chapter and served as chapter president, during which time she reinvigorated its Grants-in-Aid of Research program and created an award for post-doctoral associates to travel to conferences. She has been secretary of The Johns Hopkins University Chapter, led the national Sigma Xi Committee on Nominations, and served on the Committee on Qualifications and Membership.

Recording of Sigma Xi's Google Hangout with Melissa A. Kenney

Video Transcript:

Heather Thorstensen: Hello and welcome to this Google Hangout from Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society. My name is Heather Thorstensen. I’m the manager of communications for Sigma Xi. Today I’m speaking with Sigma Xi’s 2015 Young Investigator Award winner, Dr. Melissa A. Kenney. She is from the University of Maryland.

Dr. Kenney is a research assistant professor in environmental decision analysis. Recently, she was the lead scientist on a team that worked on recommendations for a prototype set of climate change and impact indicators for the United States. Their recommendations were instrumental in the recently released U.S. Global Change Research Program indicators, designed to help our nation begin to better understand and respond to climate change.

Those of you who are watching the hangout live can ask a question by typing it on the right side of your screen. I’ll going to be looking for questions from you toward the end of the hangout.

Melissa, thank you for speaking with me today.

Melissa Kenney: Thank you so much for having me today, Heather.

Let’s first talk about your research area. What is environmental decision analysis?

Environmental decision analysis is a social science discipline where we’re really focused on how we can help people make better decisions. I specifically focus on environmental decision analysis because I’m interested in how we can integrate multidisciplinary scientific information and societal values to inform some of our trickiest environmental challenges. I worked on a range of different topics including how we can set water quality standards, how we can restore environments to provide the goods and services that we need as a nation or as a society, and most recently how we can develop indicators to help inform really tricky climate resilient decisions.

So those indicators that you recently worked on and led the team to create the recommendations for, what initiated that effort?

That was actually initiated by a National Research Council recommendation to the U.S. Global Change Research Program. They recommended a number of years ago that USGCRP, or the U.S. Global Change Research Program, considered developing a system of indicators or a dashboard of indicators to just give the nation more of a snapshot of what’s going on with the climate and how we’re doing as a nation. That recommendation led to a series of workshops that were conducted by the U.S. Global Change Research Program and a number of federal agencies, including the Environmental Protection Agency, NASA, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Those workshops brought together hundreds of scientists to really think through how we could develop physical, natural, and societal indicators of climate changes and impacts.

From those workshops, I was a AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellow at the time, working with NOAA and the U.S. Global Change Research Program and they said "we have a research project for you to help us think through how we might be able to take some of these recommendations to help determine how we could build out an indicator system." That was a great project. I worked with a number of scientists, including my colleague Tony Janetos at Boston University. The first thing that happened was he was put as chair of a federal advisory committee indicator workgroup and through that effort we were able to collaborate with over 200 physical, natural, and social scientists across academia, the federal government, and the private sector to really think through the kinds of recommendations that we thought would create an indicator system that would be most useful for both sustained assessment activities as well as for informing decisions.

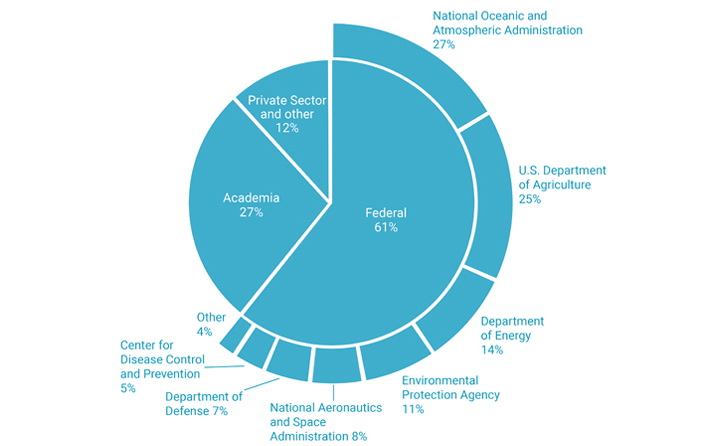

Heather, you might have an image of mine that actually shows the representation of our teams.

Photo: This chart explains what sectors, organizations, or departments were represented on the team Melissa Kenney led to create the recommendations for indicators.

Yep, let me pull that up.

Wonderful. This just gives you a sense of the level of the involvement that we had for developing the recommendations that went to USGCRP. It was a broad set of folks across nine different federal agencies, including a range of universities across the United States and then private sector, both the NGO community as well as folks from the business community. This includes traditional scientists, kind of like me, and then practitioners, who are really working on the ground, trying to implement decisions so that we could develop recommendations that are scientifically sound and useful for the challenges that we’re facing today.

Great. So once you had that group together, how did you go about starting to think about and create these recommendations for these indicators?

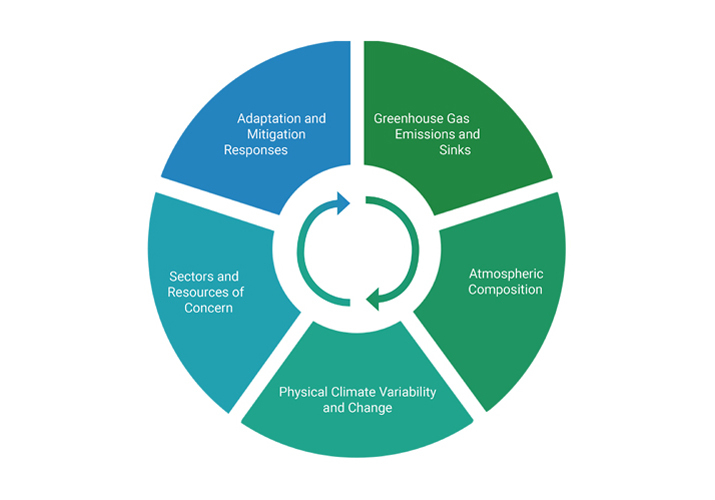

We actually decided to take a slightly different approach than what’s traditionally done. A lot of times what folks do is they survey the literature and see what indicators exist and then choose indicators given what exists or what they think should exist given various research priorities. We actually decided to do a conceptual modeling process. We did a conceptual model for our entire effort and then each of our technical teams did a conceptual model. So the conceptual model for the entire effort, Heather you might have an image for this one, too.

Photo: This is the indicator team's conceptual model.

Yep, let me get that up.

The whole goal behind the effort was we thought it would be most useful to think of developing a system of physical, natural, and societal indicators to inform and communicate key aspects of climate changes, impacts, vulnerabilities, and preparedness. This really means that we’re going sort of end to end with a diagram that you see on your computer screen. We’re going from greenhouse gas emissions and sinks through changes in atmospheric composition to changes in our physical climate system and the variability that we see on a year-to-year basis to something that actually is one of our most important contributions and something that is really unique to this effort is a pretty strong emphasis on impacts and vulnerabilities of sectors and resources of concern to the United States.

And then ultimately we want to be able to have indicators of adaptation and mitigation preparedness and responses so that we can understand what we’re doing to combat some of the challenges that we’re facing as a result of climate change and how we’re responding in the face of those challenges.

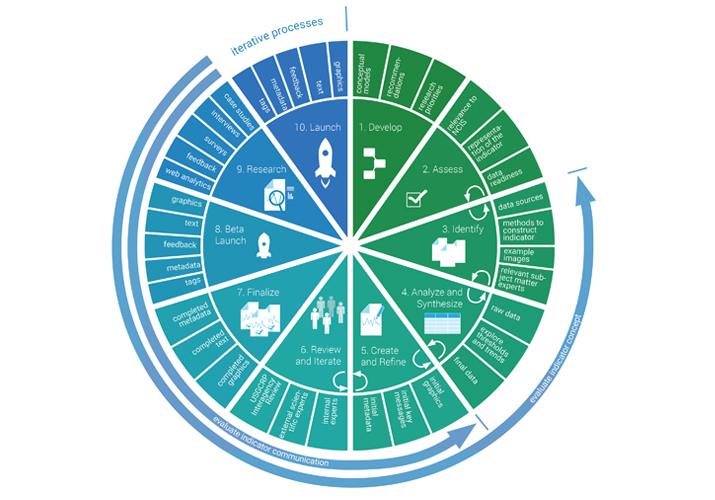

Photo: This the indicator team's process chart.

Ok. There’s one more image I have for this. I’ll pull it up so you can see if there is anything else you want to say about this process.

Oh, thanks. So one of the big things that we initially did was that vision but then the other part of it was actually figuring out how to operationalize that vision into a set of recommendations and that’s really where our teams of scientists came and played a huge role in creating the recommendations that were delivered to the U.S. Global Change Research Program.

The first pie slice that you see in this circle diagram actually describes the process of developing the recommendations. It included conceptual modeling, recommendations of indicators and data sets that already exist that could be used fairly quickly and then lastly, research priorities because we want to make sure it wasn’t constrained by just the things we can answer today given our data sets but things that we need to be answering and looking to in the future to really know how we’re doing as a nation. S

So once we had those recommendations, we had the workgroup, or advisory group that was led by Tony Janetos, assess across 14 different technical team recommendations what would be useful to build out as an entire system, what recommendations we were going to go forth and deliver. And then once we provided those recommendations we thought it would be pretty useful to develop a prototype of what we meant by an indicator, what that would look like, how we might structure just a version of that and so my research team went through the process of working with experts at federal agencies and within the broader scientific community to develop that data sets, to synthesize them, to create the graphics, to develop style guides associated with those graphics so that we could both create examples of the indicators we thought would be useful as well as processes that would be transferable if a group were to take on the indicator effort so that we could pass on the lessons learned that we gathered from just trying to create the indicators from idea to example.

So right now, what was released last week [May 6, 2015,] in terms of what USGCRP did is actually pie slice number 8, which is a beta launch, it has a baby rocket. That’s because the prototype is a proof of concept. It’s meant to start a conversation with the broader user community, citizens within the United States as well as around the world, to really think through and envision the kind of indicator system that would be most useful for both assessing the climate changes and impacts as well as providing information that would be useful for supporting climate resilient decisions.

The research piece of that is actually a piece that’s going to be done by a number of different scientists, so that’s going to be done by USGCRP scientists, my research team is doing a huge effort related to research, we have other scientists that are going to be picking up various pieces of it and the results of that research actually are going to be included in an iterative process to build out a larger indicator system that we think would be more useful, given the scientific data that we’re collecting.

This is sort of our conceptualization of the recommendations. Again, we’re providing input but USGCRP is really making the decisions. But scientists have a huge role to play, not only in this effort but in federal efforts more broadly. When input is requested, that’s when we’re asked to engaged in the policy process.

Great. I’d like to take a look at the website with the indicators on it so I’m going to pull that up here so you can walk us through it a little bit.

Sure. So the website is really exciting. Again, this is what USGCRP implemented and it actually was released on the first anniversary of the 2014 U.S. National Climate Assessment, which is a really comprehensive assessment of the climate changes and impacts that we’ve observed as well as those that we expect to see in 25 to 100 years in the United States and around the world.

The idea of indicators is that what we’d be doing is thinking through some things that we would systematically track that would be the same from assessment to assessment. It would give us, particularly for our non-physical climate indicators, a way of really being able to see change over time in a much more systematic way. And we were really excited that USGCRP liked a lot of the recommendations and the vision that we put forth for some of those ideas. We see a lot of what we provided as input included in what they adopted.

If you go to USGCRP’s website and you just search “USGCRP” and “indicators” you’ll get to exactly this page that Heather has brought up and if you click on “Browse Indicators of Climate Change” what you’ll see is a landing page and it’s not going to say anything that’s too different from what I already told you because it tells you that we want to hear from you, that this is a proof of concept and we want feedback from user communities.

As you go through, there’s a number of different indicators that are provided on this page as well as on other pages so you can kind of leaf through a whole range of them. You can see indicators that are more traditionally physical climate indicators like global surface temperatures and then you can see indicators that are a little bit more connected to impact sectors, like heating and cooling degree days, which is an indicator that’s used a lot by the building community to understand the kind of heating and cooling systems that they need to put into buildings and to estimate the amount of energy used that results from those heating and cooling decisions.

There’s also indicators that are multi-stressor in nature such as ocean chlorophyll concentration where climate is not the only stressor that causes the change that you see in that particular indicator. An indicator like that is actually a combination of changes in the climate through warmer ocean waters but it’s also a result of nutrient inputs that get put into the ocean that may increase chlorophyll levels, which are a measure of phytoplankton in our ocean waters.

Just to scroll through and give you an example, if you click to the second page, Heather, that’s right at the bottom right there, what you’ll see is there is more indicators. The first one that’s on there is actually one of my favorites. It’s the start of spring. So we’re going to click on that so you can see what someone might see if they went on an indicator page. So the start of spring is a modeled indicator so it uses a range of different data sets to estimate in a consistent way the first day of spring. It uses weather data and it also uses phenology data from citizen science groups. One of the data sets included in this is actually lilac bloom date that comes from citizen scientists. What we see from this indicator is: first, if you look at the indicator, this is an anomaly so it’s a difference from an average. And what you’re seeing is that it’s a difference from a 20th-century baseline, so 1901 to 2000 average. One of the things, if you lived in the Washington, D.C., area like I do is that you will probably remember about two years ago or three years ago it was a hundredth anniversary of the cherry blossoms, or the planting of the cherry blossoms, that was right in 2012. One of the things I remember from that is that the cherry blossom parade came after the cherry blossoms had already fallen off the trees. If you look at an indicator like this, one of the things that you notice is for the contiguous U.S., which are the lower 48 states of the United States, that across all of those states on average for 2014 the start of spring came about 10 days or more earlier than the 20th century baseline. So indicators like this can help to elucidate patterns over time as well as help us see the variability on a year-to-year basis of some of the changes that are happening across the United States.

So if you scroll down you don’t necessarily need a narrator like me to be able to [understand] all these indicators. We have key points and summaries to describe exactly what you’re seeing. If you go on to “About This Resource” there’s topics, contributors, more info, and then there’s feedback. So if you have feedback on the indicators like this one of the places where you can provide it is right down in that bottom feedback module. You can click whether or not the indicator was easy to understand and you can also provide more feedback by clicking on that button and it will pop up an email that you can type in some of the comments that you’d like us to consider.

One of the other things that I wanted to show you just while we’re in this indicator portal: Heather, would you click on “View metadata in GCIS”? It’s right where you see “more information” and I’m going to highlight this because I know we have a number of scientists on this Google Hangout. For those of us who are scientists, there’s nothing more frustrating than seeing a really phenomenal image or reading a really great paper and not being able to reproduce exactly what they have done so one of the recommendations that we made that we were so excited to see implemented was to build out a full metadata history of each of these indicators with full traceability of the data sources and exactly what was done to the original data sets so someone could exactly replicate the image that they see on their computer screen for this particular indicator. One of the reasons I think this is so powerful is that not only does it empower scientists like us to be able to recreate what was done and convince ourselves that this is interesting and useful, but it helps with multidisciplinary innovation because if I’m looking through here and I find a really interesting indicator but I’m not familiar with the data sets, I can actually go through and be able to engage with data sets that I might not be familiar with or use very frequently.

For decision makers and stakeholders, I think it’s really important that these kinds of tools not try to do everything for everyone but providing metadata systems like this one, what we’re able to actually do is provide the tools and the analytics for user communities to recreate these indicators and also be able to innovate and recreate them in ways that are useful for their own decision purposes or their own education purposes or their own communication purposes. This is really powerful and I think this is one of the innovations that we as a scientific community really need to move towards in terms of the traceability and transparency in the science that we’re conducting.

Ok. So I’m going to stop sharing it. Is there anything else you want to say about the website?

No, I’ll be happy to take questions if there is anyone that wants to take a deeper dive into any of the pieces.

Great. Can you explain a little bit about, with the different indicators, where all this data is going to be coming from?

If you take a deep dive, within each of the indicators we identify the federal agencies or organizations that provided data or indicator products for that individual effort. What you’ll see for this system as it stands right now is there [are] a lot of federal agencies listed. That’s because we as U.S. taxpayers have made really thoughtful investments in our observing networks that are really paying off now in terms of our satellites, our buoys, our ecological networks as well as our census and social science data systems that allow us to really take a deep dive and understand change over time.

As this system gets built out, our recommendations included thoughts of being able to expand just beyond federal data sources but I think the one really critical thing to keep in mind is that with any indicator effort, we think it’s really important to see change over time. And that means that you have to have some level of security that the data set is going to be sustained, that you’re going to be able to update it, and that we’re going to be able to look at this kind of indicator as more than just a single research project but more as sort of a body of change over longer periods of time.

Could you talk about why it’s so important to have this prototype set of climate indicators and what its’ going to provide us that we didn’t already have before?

A lot of you are probably pretty savvy consumers of this information so what you probably notice is that there are other indicator systems that already exist within the federal landscape as well as other organizations. A lot of those efforts focus on a lot of physical climate indicators and those are really critically important for understanding changes in Artic sea ice, the changes in our global surface temperatures as well as changes in our oceans and the sea surface temperature.

However, I think one of the things that we’ve been really lacking as a nation is a way of systematically tracking some of the impacts, vulnerabilities, and responses so that we can really understand how some of the indicators that are multi-stressor, where climate is one of many drivers that is causing the changes that we’re observing, how they’re actually changing over time and over longer time scales. Being able to set up indicators is a really nice way of identifying those things that we really care about and we want to track over longer periods of time and developing the data sets and the body of evidence to be able to sustain those over longer periods of time.

So with the prototype, this provides a proof of concept that an indicator system could be built in an interagency capacity. We’re really proud of the efforts of the various federal agencies to really come together and produce something that I think is a really critical first step for the nation. I think a lot of us are really excited to see what USGCRP decides going forward and we’re poised to provide input to make sure that it’s as useful and as scientifically sound as possible. And I think one of the ways that we’re doing that is not just the kinds of indicators that we already know need to be built out that are included in the recommendation reports that we provided already but also some of the critical priorities that we’re going to need moving forward, both in terms of the features that users identify that are going to be critical to meet their needs and to increase the utility of the information that’s being provided as well as the kinds of indicators that are really missing.

We’re really missing indicators of adaptation and what we’re doing as a nation to prepare for the changes that we’re already experiencing as well as those that we expect to experience in the future. And we also need leading indicators. If I’m a decision maker, I care about the past as it helps me to predict the future. And so being able to have indicators that are predictive of what we anticipate experiencing, with the best scientific information available with uncertainty bounds, provided in very useful ways to non-scientists I think is a really critical next step to being able to expand the indicator system to be even more useful as well as to meet the mandate of the 1990 Global Change Research Act, which is to provide predictions on 25- to 100-year timescales that are useful to the nation.

And I just want to reiterate something that I thought was so interesting about these indicators is that they’re not just about climate, they’re also about our resources like our agriculture and our land us, is that something to your set of indicators or there are already indicators out there like that?

I think there’s a lot of different indicator efforts that exist. This effort is an attempt to bring together a lot of different pieces. If you look to the U.S. National Climate Assessment, you’re probably overwhelmed to notice that there’s about 30 different chapters and that includes chapters on our physical climate system but some of the most important chapters are actually some of the chapters on our natural systems and human sectors and how climate change is impacting in a multi-stressor context those changes that we’re already observing or that we anticipate seeing.

We actually base a lot of the framing of the types of topics around the 2014 U.S. National Climate Assessment so that as the indicator system is built out, they would provide a natural entry point for sort of a small set of things that we might be systematically tracking as we conduct future national climate assessments as well as ways of identifying and providing information on I guess more scientifically determined or decision determined timescales. These National Climate Assessments, or assessments more broadly, come out after sort of a body of evidence has been produced where it’s useful to synthesize it and provide it as sort of a statement from the scientific community. However, if you look at even 2014 some of the images in there have been updated by the federal agencies or through this indicator effort as a result of new data that’s come out. So indicators actually have the opportunity to provide a more flexible framework for providing updated information as it’s available or as decision makers might need indicators to support their decisions.

And these indicators are all for the United States. Can you talk about how the indicators or how this data could be used on a global scale or how it will fit in on a global scale?

Yeah, so there’s a small set of indicators that are global context indicators, so the typical physical climate indicators that help us to understand how the climate is changing, and the future, how we anticipate it might change among longer timescales.

In terms of global efforts, we have a number of assessment activities globally like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, we’ve had huge ocean assessments, we’ve had huge biological assessments. We also have this multinational Arctic assessment that’s in the processes right now. A lot of groups are actually really interested in developing indicators so they might be able to systematically track a few things that they care about deeply. And we’ve been asked to provide some consultation about some of the processes and the thought behind the way that we developed our indicator recommendations because there’s a lot of groups that have been struggling with very much the same kinds of things and there’s a lot of different ways of approaching it. It’s not to say that there’s one method that’s better than the other, but with an eye towards assessment and decision making, we think that using a conceptual modeling approach ends up providing a really nice rigorous scientific framework for making critical decisions about what’s important to include and what’s not and being able to articulate it out to the wider scientific community so that we can have fruitful conversations based off a much more systematic tracking of what was done and why the decisions were made in the way they were.

I want to go back to talking about the team that you led because it seemed like they came from such diverse backgrounds and I wanted to know what was it like to lead such a multidisciplinary team?

Oh, it was a lot of fun. I mean, I really like doing multidisciplinary work because it means I get to ask a lot of questions and learn a lot of new things. I feel like I’m constantly a student when I get to work with so many of my colleagues that are just approaching topics in really different ways than the ways that I think about things.

It can be a little bit challenging sometimes to work in a more multidisciplinary research because sometimes we say the same word but we mean very different things. So we might say words like “mitigation” and within the climate world, we mean just greenhouse gas reductions. But within like a hazards risk reduction world, when they say “mitigation” they actually mean what we say when we say “adaptation” because they are trying to mitigate for the damages that are occurring in a community or that might be expected to occur. So there’s usually a little bit of a learning curve as we get to know the expertise that each person brings to the table and we get to know a little bit about how their particular scientific discipline expresses itself and the words they use and the ways that they think about approaching problems, whether they’re more quantitative or qualitative. But I think if we’re really going to tackle some of our toughest societal challenges, and certainly environmental and climate challenges, fall within this realm, we can’t approach it just from a single disciplinary perspective. We need to bring all the best minds to the table.

With Sigma Xi, this is a society of the best minds across the physical, natural, and social sciences and so groups like Sigma Xi actually already embody sort of a multidisciplinary perspective within its Society. I think it’s really fun also to embody that same kind of multidisciplinary perspective within our own research so that we can tackle these tough challenges that they’re really calling scientists to help lead.

When you guys had this big task before you of creating these indicators, what were some of the challenges that your team came across?

There were a number of things throughout the process. I think sometimes there is some of us, particularly those of us that like working on these multidisciplinary challenges, we often times think in box and arrow diagrams because we think in terms of systems and so that we can just see these interconnections because we like to understand the world by just mapping those. That’s a kind of a more disciplinary-specific approach. It’s sort of something that you see across certain kinds of disciplines but other disciplines approach it in a very different way so asking our teams to develop conceptual models was really difficult for some of our groups because they were just not used to developing these kinds of more system, mental models. That actually was a really interesting learning experience. I think one of the things that happened when the groups would really struggle with how they would represent the kinds of agriculture systems or forest systems is that they would really get to know each other as scientists as well as the different disciplinary perspectives and what needed to be included, and how it needed to be represented to be able to encompass such a large sort of perspective to really think through what indicators would be useful to include versus those that would not be as useful to include. So that was probably one of our biggest challenges.

My research team at University of Maryland actually took the lead in developing the proof of concept, the example indicators, to couple with the written report of recommendations so that we could both describe as well as show what we meant by an indicator system and it was really interesting moving from idea to example. In terms of ideas, you know the data sets exist and you know sometimes you could easily create it. And for some of our indicators it was pretty straightforward. Global temperature? Pretty straightforward. Other indicators, it was actually a little bit more tricky and it involved some data synthesis that was unexpected and in some cases it actually required that we really think through the story that we thought the indicator was going to tell in a very visual way because some of the recommendations worked really well for scientists but if we wanted this to be useful for citizens and non-scientists, we really had to think through how we were visually communicating the data in ways that we thought could be more easily understood. So that was also pretty tricky and it’s actually leading to some research that we’re going to be doing this summer to synthesize the visual scientific communication literature and then do some experiments to really understand whether some of the visuals that we constructed communicate better than the original ideas as well as how we might even revamp some of our examples into things that we think would communicate better and then experimentally test whether or not that actually happens.

What about the success moments on your team, when you were just thinking “yes, this is why we brought everybody together”?

I think there were a couple. So I think with a lot of these efforts, being able to meet in person ends up being just so critical and usually on the second day of those in-person meetings, there were like these breakthrough moments when you’re like, “Oh good, I thought this might fall apart but now it seems to be holding together, I think we’re Ok.”

And then, you know, last week when USGCRP released the indicators was definitely a celebratory moment for all of our 200 scientists because it’s really rare to be able to produce something and actually see it come to fruition and it was just really powerful to actually see that happen. I think oftentimes we develop our proposals and we write reports where you write peer-review manuscripts but we wonder if it sometimes goes into a black hole and it never gets seen by someone and, I don’t know about some of you guys, but I really got into science because I wanted to not only investigate interesting questions that had never been answered but I also just really wanted to do something that would help society, and particularly help make sure the environment was as good or preferably better than when I came onto the Earth.

And so being able to see that we’re able to provide rigorous scientific information that might actually help people to make some really tough environmental decisions I think is a really powerful moment for both me as well as the scientists that we all worked with.

As we were going through the website, you were showing how people can provide their feedback. And I’m wondering why it was so important for you to have that opportunity to give that feedback and if there is a deadline of when people get to need to get that feedback in by?

I think with any of these indicators first impressions are always really useful and so we wanted to provide an easy way for people to provide sort of their first impressions of these kinds of indicators and to open up more than just to the community where our research studies might allow participation. This is only one of a series of ways that we’re hoping to involve user communities. I know we’re doing some understandability surveys, like do people actually understand the indicators that were produced and can they answer some fairly straightforward questions that one would think they would gather from the visual that they’re seeing to surveys and focus groups and semi-structured interviews and case studies where we’re really taking a deep dive to see how people are using indicators to structure their decisions, to inform their decisions, and potentially to create innovations of sort of multidisciplinary research that wasn’t envisioned previously to seeing some of these kinds of products. We’re really looking forward to, at least our research team, sort of expanding this scope.

But the feedback module is just one piece of it and there’s not natural deadline to that feedback. As you look at things and engage or reengage with the information, please feel free to provide that input because I think the more perspectives that we get, I think the better it is and those kinds of comments end up being really helpful for refining the way that the indicator system is developed and the kinds of recommendations that we would make to USGCRP and other efforts doing climate decision support moving forward.

And so as you think about working on more indicators in the future, or improving the indicators, is there anything that you are already thinking that maybe is missing and could be incorporated?

Oh yeah, absolutely. With 14 indicators and a really large mandate, what you see on the USGCRP website is a snapshot. You know, it’s 14 of probably a couple hundred indicators that were coming out in recommendations. So we’re doing a couple of things. One is we’re actually in the process of refining these recommendations and research priorities so that we can publish it as part of a special issue of a journal in the upcoming year or two.

We’re also really looking forward to reengaging or engaging a new set of scientists and thinking through two really complex challenges. One is adaptation indicators. How can we develop a set of indicators that can really assess how we’re preparing as a nation and we’re responding to some of the climate impacts that we’re already experiencing? So, really getting a sense of what we’re doing and whether it’s working. That’s one of those things that ends up being easy to say and a little bit hard to do because folks have been doing it on a project by project basis but if you want to think about it at a national scale and say “how are we doing as a community,” “how are we doing as a state,” “how are we doing as a nation” it gets increasingly complex as we think about these different scales.

The other really big question that I’m totally jazzed about is thinking about leading indicators. These are indicators that are predictive of future conditions. So I think I might have mentioned earlier that if I’m a decision maker, I really only care about what’s happening today and in the past as it helps me to understand the future because the decisions I’m making are usually decisions that are going into the future and as a result, being able to understand the timescales where folks are trying to look out to in the future, whether they are seasonal, annual, multi-year or decadal timescales so that we can figure out indicators at the right time set, to be able expand our set and the way that we are thinking about it, as well as the kinds of indicators that would be really useful to develop.

I think there’s a number of really great leading indicators using climate models that give us a sense of temperature change or potentially precipitation change in the future. I think there’s real opportunities to think about real impacts on our natural systems in human sectors because a lot of our adaptation decisions really require knowledge of those kinds of impacts and vulnerabilities to be able to make smart decisions. So we’re looking forward to really expanding our work in that arena. Stay tuned because it’s just starting right now.

And you’ve brought in undergraduate students and science policy fellows who are predominately female or from underrepresented groups to join your team. And I’m wondering what kind of research experiences they get when they join your team?

So when you do science policy research, it’s a little bit of a different kind of laboratory so we’re not having them wash glassware or conduct titration experiments. Instead, a lot of the students are actually taking deep dives and learning how to synthesize the literature, how to potentially code different research reports or efforts that they’re developing. They may be coordinating different scientific teams so in the past couple of years, I told you we had 14 different teams, a lot of our students or fellows were instrumental in making sure those teams were successful because similar to making sure that your soil samples are labeled properly, if you’re not effectively coordinating groups of 14 different scientists to be able to meet effectively and then also develop the notes and summarize it, you haven’t actually developed your “lab book” in a useful way for these kinds of multidisciplinary scientific products.

In some cases, we’ve had PhD students who have developed dissertation projects looking at stakeholder engagement and various indicators that they found personally interesting to construct and so the projects really ranged. And actually the disciplinary background of our students really ranged. We have anthropologists, we have political scientists, we have economists, we have climatologists, we have ecologists. I mean, I think the kinds of students that end up being really attracted to this kind of multidisciplinary research is as diverse as the kind of expertise that we have on the teams but I think what brings us together is thinking of how we might be able to address some of these tricky problems in an interesting and novel way.

And I just want let everybody know who is watching live know that we’re coming to the end. This the last question I have for Melissa so if you have a question, don’t forget that you can type it into the right side of your screen and I’ll ask for it.

So Melissa, I wanted to go back to talking about your Sigma Xi connection. You have a really strong connection with Sigma Xi. You were a chapter leader at Duke and Johns Hopkins and now you’re part of the University of Maryland Chapter and you’ve also led and served on some national committees and I was wondering how Sigma Xi has played in in your perspective to your scientific career?

I think Sigma Xi is like a really special society because it really is all of the scientific disciplines and what brings us together is a love of scientific research and sort of the inquiry behind us, behind sort of that scientific discovery and innovation. But I think also, some of the things that unite us are a love and desire to make sure that that science is serving society in some useful way and so it’s been a real honor to be a part of Sigma Xi, first as a graduate students where I was totally jazzed to be inducted into this society and become an associate member, all the way through serving on national committees where we were trying to shape the direction of the society in ways that we thought might be useful for the future.

So if any of you guys aren’t Sigma Xi members I hope you take a look at the Society and see whether it is something that is exciting to you as much as it’s exciting to me.

Thanks, Melissa. I don’t see any questions from the audience so I just want to remind everybody that Melissa will be speaking at Sigma Xi’s Annual Meeting where she will accept her Young Investigator Award. That meeting is going to be October 22–25 in Kansas City, Missouri. Melissa, thank you very much for talking today.

Thank you so much, Heather, and thanks everyone for joining us.

Bye.

Bye.